Our research

Proteins are the building blocks of living things, miniature motors that make all of your cells function. Proteins embedded in cell membranes filter out toxic materials or uptake necessary nutrients. Short proteins called peptides help your immune system fight off bacteria, while super long proteins called mucins form into the protective hydrogel coating we call mucus that controls what can enter our bodies in our eyes, lungs, and gut. Meanwhile, malfunctioning proteins are implicated in a slew of disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, type II diabetes and cystic fibrosis. Our group works on understanding and designing proteins and peptides for biomaterials and therapeutic applications. We use a combination of machine learning techniques and computational modeling techniques such as molecular dynamics simulations.

Machine Learning for Peptide Design

We’ve all heard of the power of artificial intelligence. And it’s true that computers are very fast at sifting through astronomical amounts of data to find or match patterns! But AI techniques are only as good as the data that informs them and the experts who use them, and this is something we all try to keep in mind. In my lab, we develop machine learning-based workflows for peptide design. We strive to create models that are rigorous and understandable and to do so in a societally-informed way. Below, I talk about two of our current favorite applications.

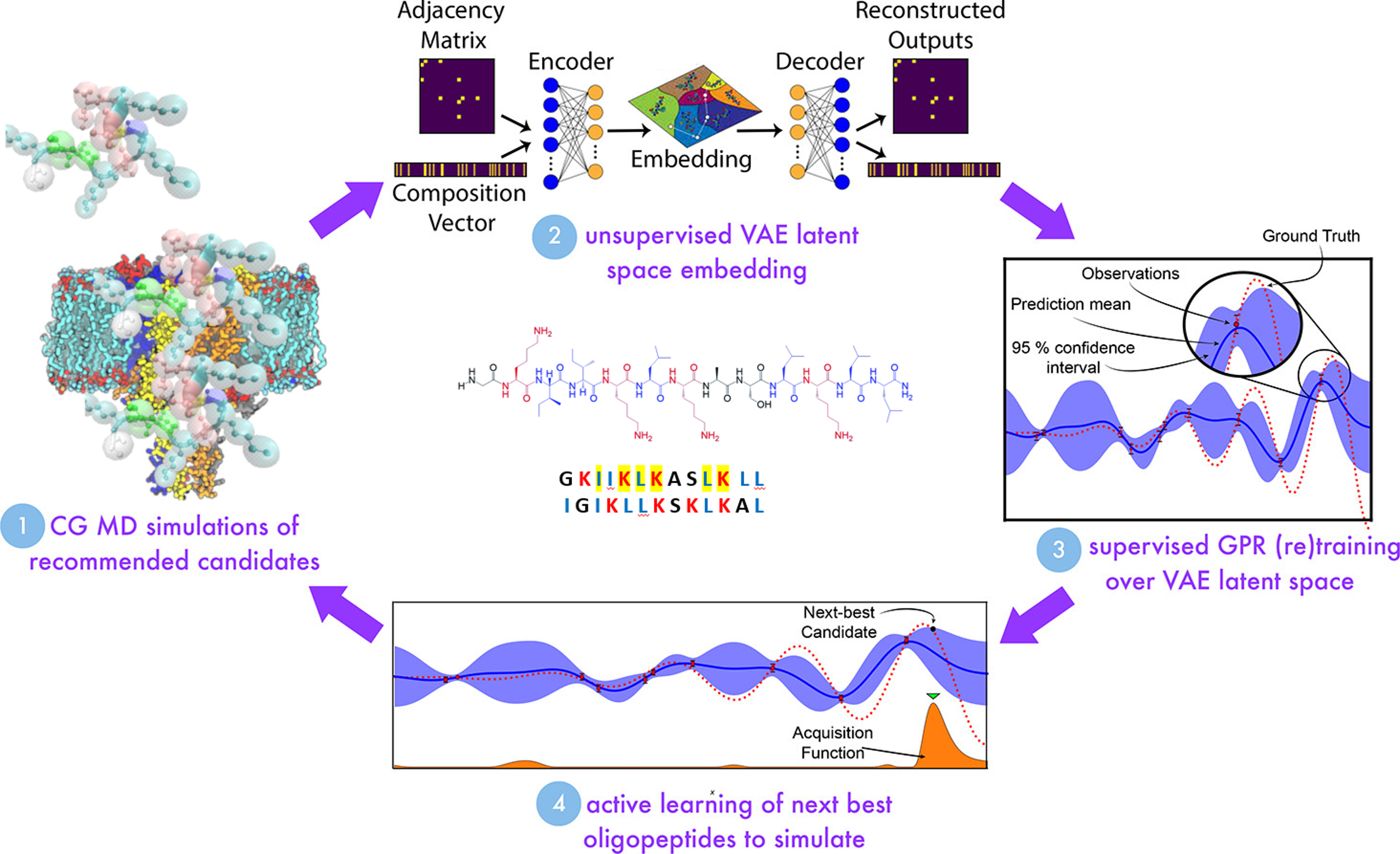

<figcaption> Schematic of AMP design in the Mansbach Lab. Some aspects of the image are modified from Shmilovich, Kirill, et al. “Discovery of self-assembling π-conjugated peptides by active learning-directed coarse-grained molecular simulation.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 124.19 (2020): 3873-3891.

</figcaption>

</figure>

<figcaption> Schematic of AMP design in the Mansbach Lab. Some aspects of the image are modified from Shmilovich, Kirill, et al. “Discovery of self-assembling π-conjugated peptides by active learning-directed coarse-grained molecular simulation.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 124.19 (2020): 3873-3891.

</figcaption>

</figure>

Antimicrobial Peptides

All things strive to live, and bacteria are no different. When we kill them with antibiotics, some few have mutations that allow them to survive those drugs, and they go on to reproduce, growing the capacity of a bacterial population to be resistant to antibiotics like penicillin. Antimicrobial resistance is a growing global health threat that disproportionately affects lower and middle-income countries. In my lab, we are trying to develop peptides that can kill bacteria or ameliorate their toxic effects while possessing properties that mean bacteria grow resistance to them more slowly.

We investigate the development of machine learning models to map out design spaces for such antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). Employing both traditional ML models such as support vector machines and generative deep learning models such as variational autoencoders, we assess the design spaces associated with different algorithms. We strive for interpretability, controllability, and the ability to rapidly zero in on peptides of greatest interest.

We also perform detailed biophysical characterization of specific candidate peptides of interest. Unlike many large proteins, shorter peptides tend not to be associated with a single native structure, but with a structural ensemble that changes according to environment. This set of accessible structures is responsible for their functions. AMPs, in particular, are often disordered in solution but fold into alpha helices or beta sheets near bacterial membranes, which often affords them the capacity to disrupt the membrane.

One of our most carefully-studied peptides is the AMP GL13K, which is a unique non-toxic peptide that both attacks the cell membranes of bacteria and can also protect the host to a degree against the bacterial endotoxin LPS. We perform simulations of GL13K and other candidate peptides under different conditions, to understand their structural ensembles and the mechanisms by which they interact with bacterial and host cells. Our goal is to identify properties responsible for membrane disruption, such that we can design peptides with properties that confer bacterial disruption capability or capabilities that protect against bactieral toxins and lacking properties that confer membrane disruption capability.

<figcaption> Searching through a deep learning associated design space. Image created by Jyler Menard.

</figcaption>

</figure>

<figcaption> Searching through a deep learning associated design space. Image created by Jyler Menard.

</figcaption>

</figure>

Amyloid Scaffolds

Many peptides can form the distinctive cross-beta sheet fibrillar structures (amyloid fibrils) that are a hallmark of certain pathologies, such as Alzheimer’s disease. But did you know that peptides that are intended to fold into such a structure can actually be beneficial? They can help us deliver drugs, form scaffolds for cell growth, or be part of nanovaccines! We recently started a collaborative project with the Bourgeault Lab at UQAM, in which we are trying to use well-established active learning techniques and search through the latent space of our previously-developed generative deep learning models for peptide sequence design, to try and find sequences that can controllably form into amyloid fibrils.

Toxins and toxin-based therapeutics

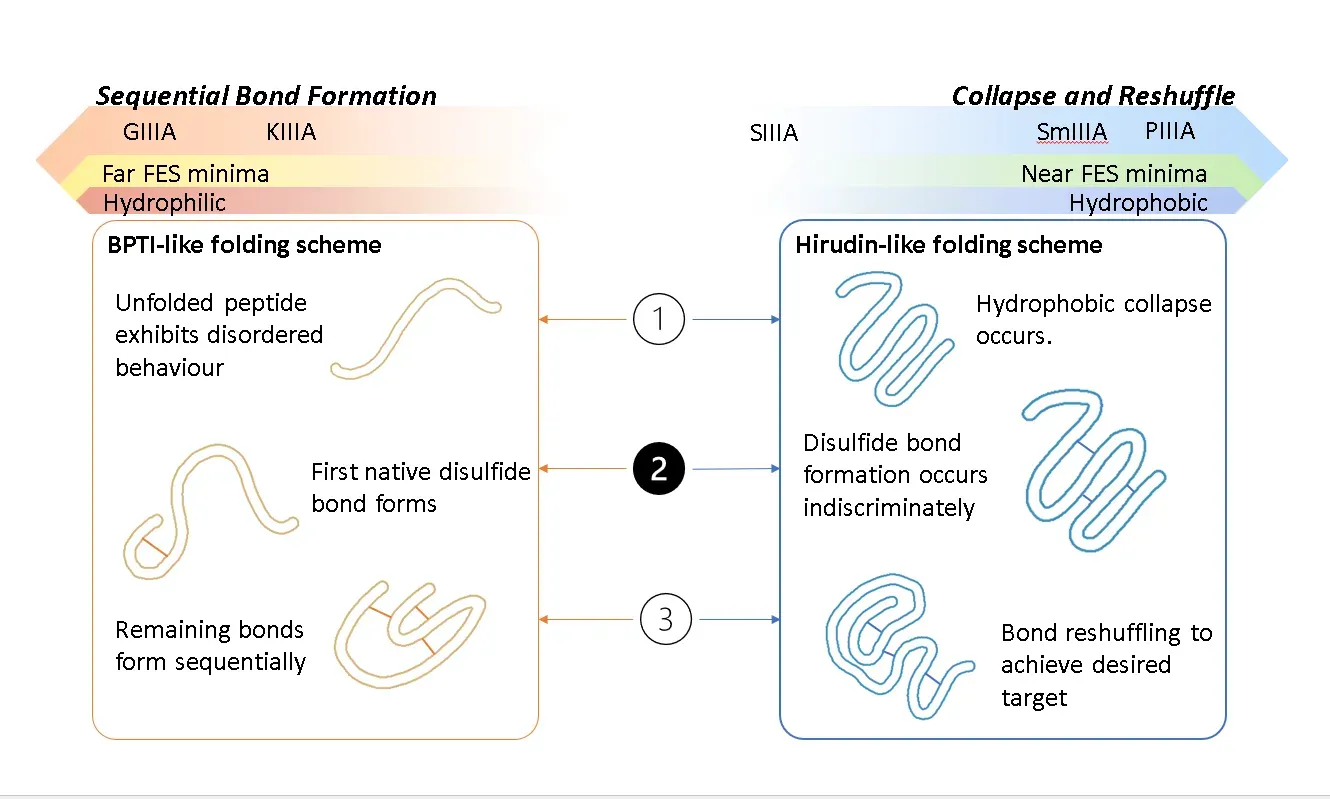

Owing to their high specificity and binding affinity for various receptors involved in different biological pathways, toxins have for a long time been considered a rich natural source of therapeutic leads. A large and intriguing class of toxins is those that are short, cysteine-rich peptides whose structures are largely controlled by the multiple disulfide bonds that form between the cysteines. Historically, one difficulty in assessing the structure and hence the proposed mechanisms of such toxins has been that it can prove difficult to controllably fold them to their native stable states in vitro. Indeed, there is evidence that certain toxins exist even in vivo in metastable states that are nonetheless potent and in certain cases the “non-native” fold demonstrates higher selectivity and binding affinity which leads to the question of whether we can control these metastable states through sequence, environment or kinetic engineering. We are exploring ways to map out the free energy landscapes of disulfide-rich toxins.

</figure>

</figure>

Aspect of toxin folding. Image created by Natalya A. Watson, copyright 2023.

Multi-scale modeling of mucus

A major component in bodily health is mucus–the slimy gel that forms a protective coating on many outer surfaces. It is actually composed of a large number of organic components, but one of the major building blocks is the “mucins,” a family of proteins containing two unusual characteristics. They have the ability to aggregate into gels through chemical bonds between their cysteine residues, and they are covered in long, branching sugars called glycans, which affect the resulting properties of the gel.

Biomimetic materials–materials that are designed to mimic biological substances–have a number of advantages in many technological design realms. To name a few, they are generally non-toxic and low-cost to manufacture, since they can be created under non-extreme conditions, such as in water or at room temperature. Glycosylated proteins–proteins covered in glycans–have recently been used for applications such as biocompatible glues and antifreeze.

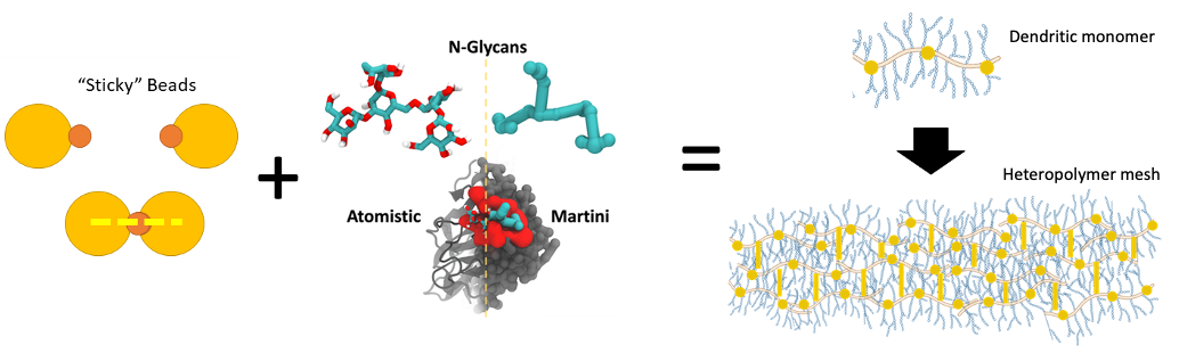

In our lab, in collaboration with the Chakraborty Lab at Northeastern University, we are devising a multi-scaled model of mucin-like proteins. Bringing together atomistic molecular dynamics, chemically-specific coarse-grained models with the Martini force field, and soft polymer models, we investigate the effects of sequence and length on the gel-like properties of different mucins. In the future, we hope to design novel hydrogels.

</figure>

</figure>

Multi-scale model of mucus. Some aspects of the image are modified from S. Chakraborty, K. Wagh, S. Gnanakaran, and C. A. López, “Development of Martini 2.2 parameters for N-glycans: a case study of the HIV-1 Env glycoprotein dynamics,” Glycobiology, vol. 31, no. 7, pp. 787–799, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwab017.

Network theory and deep learning

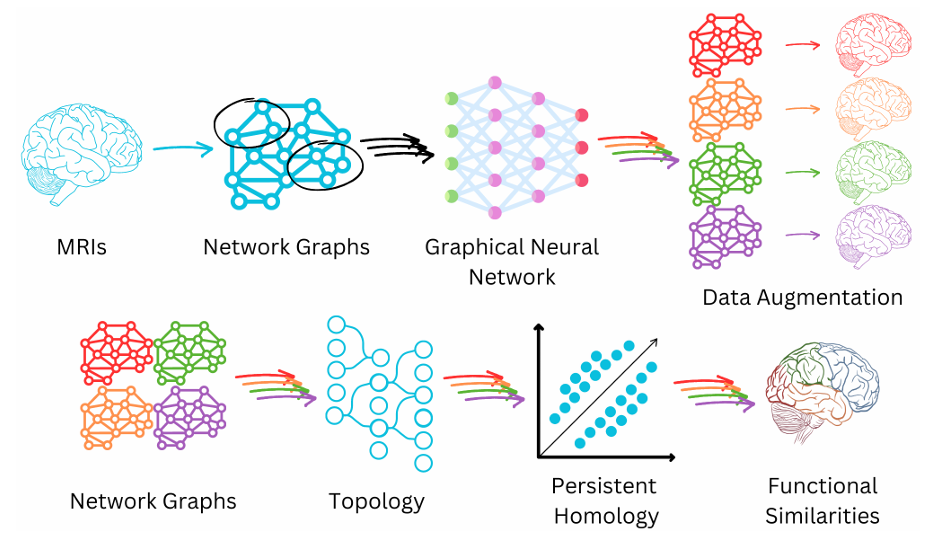

Our lab is fascinated by network theory, also called graph theory, which is the theory of how groups of things are connected. It is applicable to a large number of different domains in science. I have previously studied network theory to develop methods for identifying communities in networks – groups of things that are more connected with one another than with other groups. I was also fortunate enough to be involved in using network theory to understand the behavior of the SARS-CoV2 Spike protein, which is responsible for viral entry into host cells. Our lab searches for different applications of network theory. So far, we are investigating its use in deep learning data augmentation for MRI imaging of sufferers of long COVID (a collaboration with the Gauthier Lab at Concordia University), and we are also beginning to look into how it may be applied to understand the properties of deep learning neural networks themselves.

</figure>

</figure>

Schematic of MRI imaging, long COVID project. Image created by Lindsay N. Wright, copyright 2024, all rights reserved.

Simulations of photosynthetic proteins

A better understanding of photosynthesis, the process whereby living systems convert solar energy into chemical energy, is a crucial process in our world. Understanding it has important implications for renewable energy sources research and in for designing more resilient organisms that can survive in more stressful conditions arising from climate change. We have an ongoing project in collaboration with the Zazubovits Lab at Concordia University, in which we are performing molecular dynamics simulations and quantum calculations to understand the properties of photosynthetic proteins.